Wednesday, February 27, 2013

Two Scollay Scenes

I fell in love with this 1860 photograph of a horsecar passing by Pemberton square along Tremont Row.This is Scollay square wayyy back in the day. The day in this case is pre-Civil War days, when the horse car was a new conveyance on the streets of Boston. Just a few years before this photograph was taken, there were no rails in the streets, and passengers would have been riding in omnibuses, which were long, multi-passenger coaches pulled by a team of horses. With the use of rails, horses were able to pull significantly more weight, and cars got larger.

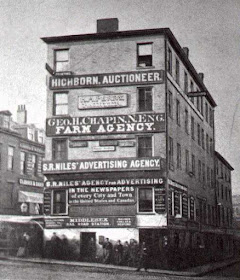

Scollay's building, very near the time of the top photograph, and just before it was taken down in 1870.. Both photos show the sign for the Middlesex Railroad, which operated the horsecar line shown above, which ran to Cambridge.

When I first saw the top photograph, I wondered if I could identify S. R. Niles. Sure enough, Stephen R. Niles showed up in the 1855 Boston Directory at 1 Scollay's building. And the 1865 Directory identifies him as an advertising agent, with a home at 17 Pinkney street. The city took the building to open the street in 1870, and in 1870 Niles' business is located at 6 Tremont street.

George R. Hichborn, auctioneer, first appears in the Boston Directory in 1855 at 10 Faneuil Hall. In 1865, Hichborn (and son, apparently) are in the Scollay building as seen above. In 1872, the building has been removed, and Hichborn & Co. is at 63 Court st. They were still present at that address in 1885, but by 1905, the company is not listed, and Samuel Hichborn is principal assessor in City Hall.

George H. Chapin doesn't appear in the 1865 Directory, showing up in 1870, just as the building is going to be taken and pulled down. This dates the second photograph above (if we can trust the directories) to a date between those two years. Google informs me that the farm agency was a real estate agency selling farms. When Scollay's building came down, Chapin moved to 24 Tremont Row, basically across the street. In 1885, Chapin is also listed as a publisher, and is located on Washington street, and in 1905, the listing is 'real estate and publisher' - no mention of farms any more - although in 1925, it's back to 'farm agency.'

Scollay square, with the Scollay building, marked in red, 1851 (BPL).The top photograph look from a building at Cornhill and Court streets, past the Scollay building, across Tremont Row and up Pemberton to Pemberton square.

If you're interested in Scollay square, make sure you visit this great blog.

Sunday, February 17, 2013

William Ladd Taylor's Washington Street

Busy Washington Street Scene, 1901, W.L. Taylor (BPL Flickr photo group).

W.L. Taylor was a painter and illustrator whose work was featured in The Ladies Home Journal. He was born in 1854 in Grafton, and studied art in Boston and New York. In the 1880s, Taylor had studios on School and Boylston streets in Boston, and was a member of various art clubs and societies.

Of interest to A.T.I.G.O.B. is the print featured above. I like to think that this print represents what we would have actually seen on a busy day at the turn of the 20th century. With the slow transportation of the day, pedestrians did cross the street as they pleased, and ragamuffin newsboys crossed paths - though not fates - with finely dressed ladies and their equally finely dressed children.

Beyond a look at the contemporary fashions, this print gives us a summary of downtown transportation. I wonder if the artist meant to put the electric streetcar directly between the horse carriage on the right, and the very new automobile on the left. And perhaps it's a coincidence, but the carriage, with it's driver at the top back, is reflected by the auto, which in this model also has its driver in the rear position, overlooking its passengers.

Sadly, we probably have a better sense of Victorian London than we do of the contemporary Boston. If only from Sherlock Holmes, we see the world of hansom cabs as being British, whereas our own cities would have appeared very familiar to Holmes and the rest of Victorian Britain's great literary characters. Unfortunately, while British writers explored their urban capital, Americans looked west for inspiration. And late 19th century America becomes the story of Cowboys and Indians, rather than Boston/New York/Philadelphia city dwellers. Henry James does write of Bostonians, but he chases them to Paris, and has no interest in the North End or South Boston.

Wouldn't you love to see a movie set in the Boston on 1901? If CGI can create alien planets for Hollywood, why not turn of the century Boston, with streetcars and carriages and automobiles all fighting to get through throngs of shoppers on Washington street?

W.L. Taylor was a painter and illustrator whose work was featured in The Ladies Home Journal. He was born in 1854 in Grafton, and studied art in Boston and New York. In the 1880s, Taylor had studios on School and Boylston streets in Boston, and was a member of various art clubs and societies.

Of interest to A.T.I.G.O.B. is the print featured above. I like to think that this print represents what we would have actually seen on a busy day at the turn of the 20th century. With the slow transportation of the day, pedestrians did cross the street as they pleased, and ragamuffin newsboys crossed paths - though not fates - with finely dressed ladies and their equally finely dressed children.

Beyond a look at the contemporary fashions, this print gives us a summary of downtown transportation. I wonder if the artist meant to put the electric streetcar directly between the horse carriage on the right, and the very new automobile on the left. And perhaps it's a coincidence, but the carriage, with it's driver at the top back, is reflected by the auto, which in this model also has its driver in the rear position, overlooking its passengers.

Sadly, we probably have a better sense of Victorian London than we do of the contemporary Boston. If only from Sherlock Holmes, we see the world of hansom cabs as being British, whereas our own cities would have appeared very familiar to Holmes and the rest of Victorian Britain's great literary characters. Unfortunately, while British writers explored their urban capital, Americans looked west for inspiration. And late 19th century America becomes the story of Cowboys and Indians, rather than Boston/New York/Philadelphia city dwellers. Henry James does write of Bostonians, but he chases them to Paris, and has no interest in the North End or South Boston.

Wouldn't you love to see a movie set in the Boston on 1901? If CGI can create alien planets for Hollywood, why not turn of the century Boston, with streetcars and carriages and automobiles all fighting to get through throngs of shoppers on Washington street?

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

Charlestown State Prison

Early print of Charlestown Prison - looks like the illustration of a Poe story.

Charlestown, showing the prison and the new Prison Point bridge 1818. (All maps, Norman B. Leventhal Map Collection, Boston Public Library)

At the turn of the 19th century, Boston as it existed at the time was already criss-crossed with streets and built out. The Mill Pond had yet to be filled in, and the waters of the Back Bay came up to the edge of the Common. Yet Boston and the state had grown in population, and needed new and larger institutions to keep up with their growth. Soon after annexing South Boston, a large plot of land was bought to locate Boston's new School of Reformation, House of Industry, House of Correction, and Lunatic Asylum. When the state had need for a new prison around the same time, nearby Charlestown was chosen for the site.

Charlestown State Prison, 1850 from the American Folk Art Museum.

Charlestown Prison, 1838. The land around the Craigie bridge has been filled from Lechmrere Point to the Prison Point bridge. The Lowell Railroad had built a branch line over to Charlestown, from upper right down across the Prison Point bridge.

The site chosen was along the waterfront at Lynde's Point. At the time, as shown in the maps above, a bay extended back between Charlestown and Cambridge. The first prison was built in 1805-6, and began accepting convicts. I'll interject here that the Prison Point bridge seen on the maps was first planned as a tidal dam around the same time as the prison. After delays due to financial difficulties, the project shifted from being a dam from Lechmere Point to Charlestown, and became a bridge from the Craigie Bridge to Charlestown at the prison.

This 1859 map shows the proliferation of railroad line coming up from depots on Causeway street and past the edge of Charlestown to points north and west.

Additions were built in the 1820s and 1850s, as prisons went through a period of reform. The 'reform' may have been bad for the prisoners, as it involved a turn to total isolation and silence during the day. No prisoner was allowed to speak to another prisoner, and the elimination of much petty corruption meant that prisoners could no longer bribe guards into allowing small favors. Prisoners were even prevented from sending or receiving letters to or from family. It did prevent violence among prisoners, and allowed them to serve their time in peace, if they could deal with the social isolation.

Charlestown Prison, 1885.

Charlestown prison guards, 1896. Apparently, obesity is not a recent thing.

Twentieth century view of the prison entrance.

Last but not least, the electric chair at Charlestown State Prison, 1909.

And yes, Charlestown State Prison became the home of the states' electric chair. Luigi Storti was the first to be executed in the Massachusetts electric chair, in December of 1901. Sacco and Vanzetti. The last state executions were of Phillip Bellino and Edward Gertson in May of 1947.

Charlestown and prison, 1928 BPL Leslie Jones collection. (Click link for full size photo).

During the 1850s, the prison was seen as an overcrowed mess, and a new prison was built in Concord. After several years, for reasons that aren't clear to me, the prisoners were moved back to Charlestown. In 1956, a new state prison opened in Walpole, and the prisoners from Charlestown (then the nation's oldest prison) were moved there. Bunker Hill Community College opened on the site of the Charlestown prison in 1973.

Sunday, February 10, 2013

Boston Boys and their Winter Games - 1850s

For your winter enjoyment:

A favorite book of mine is Old Boston Boys and the Games They Played, by James D'Wolf Lovvett. Published in 1906, it looked back on childhood (or rather boyhood) during the pre-Civil War years of the 1850s. The boys featured were Beacon Hill boys, although the adventures of West and South End boys enter the story. It's the story of Yankee boys, when there seemed little need yet to discriminate among Boston's ethnic mix. There are 'colored' people present, residents of the back of Beacon Hill, and perhaps the West End, and 'Hibernians' and Italian vendors gain a mention, but to the author, Boston boys are the sons of Yankee Beacon Hill.

"Just over a low ridge of ground, which is now Arlington street, was the "Back Bay," a sheet of water that extended from the Mill Dam to Boston Neck, and many a time we boys struck straight across upon the ice from the corner of Arlington and Beacon streets, to where Chickering's piano factory now stands."

I pulled out this single sentence about ice skating on the ice of the Back Bay to feature. The 1852 map above shows the degree to which the South End had already been filled. It also shows the Back Bay before it was filled, with two railroad line criss-crossing it on timber trestles. Note that the Back Bay was not entirely open water - there were apparently low islands of grass. Assuming this map to be correct, I suspect the boys setting off from the corner of Arlington and Beacon streets would have been forced to skate around the large island between there and the later site of Chickering's piano factory. In fact, Chickering's is shown here near the end of a sliver of water, and probably beyond where the boys skated.

Note also that there is no mention in the quote above of skating under the railroad trestles, which would have been required of anyone skating between those two sites. The blue line shows the most likely route followed by the skaters, from the edge of the Public Garden, under the Boston & Providence trestle, and then turning right and running between that trestle and the shore of the South End, under the Boston & Albany trestle, and on as far as open ice allowed. The author comments that to go the other way, towards Gravelly Point and the dam, one would approach fast running water as the tide shifted, which kept the ice thin or entirely open, and thus was a great danger.

And now, from skating to coasting:

Of course, the winter sport par excellence was coasting, and those Boston boys whose boyhood was at the zenith in the fifties include coasting, as it was then practiced, among the lost arts. If any of the youngsters of to-day are inclined to laugh at this statement, let any one of them, athlete though he may be, take a running start of from three to ten yards at full speed with the sled following at the end of its cord, and when sufficient impetus has been acquired, throw it ahead, letting the line fall along the seat, at the same time launching his body, curved bow-wise, forward through the air, alighting breast first, with no apparent effort, jar, or retardment of speed as softly as a falling snowflake, upon the flying sled as it shoots underneath. This would be called pretty, acrobatic feat to-day, but was too common then to attract special notice. That's the difference.

All coasting in those days was racing, pure and simple. Prominent sleds were as well known among the boys as race horses and yachts are today, and on any given Saturday afternoon hundreds of spectators might be seen hedging in the "Long Coast," which ran from the corner of Park and Beason streets to teh West Street entrance and as much farther along Tremont Mall as one's impetus would carry him. A squad of coasters would be bunched together at the top of the coast, holding their sleds like dogs in leash, waiting for some "crack" to lead off. As he straightened himself and started on his run with the cry of "Lullah!" to clear the way, it was the signal for all to follow, and one after another would string out from the bunch after him, in rapid succession, each keen to pass as many of those ahead as possible,the lesser lights being careful not to start until the "heavyweights" had sped on their way.

The walk back uphill was made interesting by discussing the merits, faults, lines, etc., of the noted sleds, and if, as often happened, invidious comparisons were made between a "South End" and a "West End" sled, a lively and not altogether unwelcome scrap, then and there, was usually the logical outcome.

Sleds (the first-class ones) were made with much care and skill, and cost proportionately. Natural black walnut was a favorite material, finished either with a fine dead polish or a bright surface, varnished with as much care as a coach; the name, it it bore one, was usually a fine specimen of lettering in gold or bright colors. The model was carefully planned, and the lines were graceful and a delight to teh eye of a connoisseur. Black enameled leather, bordered by gold or silver headed tacks, made a popular seat, and the "irons," as they were called, were made of the best "silver steel," whatever that meant. They were kept burnished like glass, with constant care and fine emery and oil, and a streak of ashes or a bare spot was avoided as a yacht steers clear of rocks.

The amount of "spring" given to the irons was also a matter of moment, and a nice gradation of the same was thought to have influence on the speed; it certainly added greatly to one's bodily comfort.

"Let's see your irons" was a common request, and the owner thus honored would jerk his sled up on its hind legs, so to speak, wipe ff the steel with mitten or handkerchief, and show off the bright surface with much pride.

The most popular coasts were the "Long Coast' already mentioned, the Joy Street coast, Beacon Street Mall, and the "Big" or "Flagstaff" Hill, the flagstaff standing on the spot now graced by the Soldiers' Monument. The hill was much higher than it is now, the ground around it having been raised in recent years. Many of the boys will recall the evenings spent on Mount Vernon and Chestnut streets and Branch avenue, - the latter known as "Kitchen" street.

Fancy a laughing, shouting crowd, in these days of police surveillance, coasting down public streets until eleven o'clock at night! But the Civil War came and changed many things, coasting among the rest. Most of the laughing, careless crowd enlisted at the first note of the country's call, and their boyhood came to a sudden end as the sound of drum and fife stirred all hearts to sterner things. Some came back, but many, alas, stayed behind with the great silent army, and it is for us who are left to keep their memories green until we too are enlisted in the same ranks.

It will, I am sure, be of some interest to may who remember those days, to see once more the old familiar names of a few of the crack sleds of Boston at that period, and to have recalled to their minds who the owners of them were.

Wivern - Bob Clark

Raven - Arthur Clark

Brenda - Dan Sargent

Charlotte - Alfred Greenough

Comet - Frank Wells

Southern Cross - Frank Lawrence

Eagle - Jim Lovett

Arrow - John Muliken

Wild Pigeon - Ned Kendall

Tom Heyer - Jack Carroll

Titania - Nate Appleton

Multum in Parvo - Frank Peabody

Cave Adsum - Ned Amory

Dancing Feather - Charlie Greenough

Flying Childers - Frank Wildes

Juniata - Horace Bumstead

Trustee - Charlie Chamberlin

Santiago - Dick Robbins

Whiz - Will Freeman

Flirt - Horace Freeman

Scud - Eben Dale

Flying Cloud - Billy Fay

Cygnet - Jim Chadwick

Alma - Fred Crowninshield

Tuscaloosa - Horatio Curtis

Viking - Edgar Curtis

Moby Dick - Henry Alline

Of course there were many sleds equally fine which bore no name; prominent among this latter class should be mentioned the one owned by Tom Edmands and also one which was made and owned by Charlie Lovvett, both of them beautiful in grace, workmanship, and finish. There was one sled, named the "Edith," which always appealed to me as being more nearly perfect than any that I can remember. I cannot recall the owner's name, but I fear that whenever I saw this sled the tenth commandment was handled pretty roughly.

I can well imagine the boys and the pride they took in their sleds. The names sound like sailing ships - so romantic. I found a single reference to Tom Heyer as America's first boxing champion, although it will take some off-line digging to verify and elaborate on the fact. The reference to the 'great silent army' put a lump in my throat, and made the entire passage worth reading on its own.

A favorite book of mine is Old Boston Boys and the Games They Played, by James D'Wolf Lovvett. Published in 1906, it looked back on childhood (or rather boyhood) during the pre-Civil War years of the 1850s. The boys featured were Beacon Hill boys, although the adventures of West and South End boys enter the story. It's the story of Yankee boys, when there seemed little need yet to discriminate among Boston's ethnic mix. There are 'colored' people present, residents of the back of Beacon Hill, and perhaps the West End, and 'Hibernians' and Italian vendors gain a mention, but to the author, Boston boys are the sons of Yankee Beacon Hill.

"Just over a low ridge of ground, which is now Arlington street, was the "Back Bay," a sheet of water that extended from the Mill Dam to Boston Neck, and many a time we boys struck straight across upon the ice from the corner of Arlington and Beacon streets, to where Chickering's piano factory now stands."

I pulled out this single sentence about ice skating on the ice of the Back Bay to feature. The 1852 map above shows the degree to which the South End had already been filled. It also shows the Back Bay before it was filled, with two railroad line criss-crossing it on timber trestles. Note that the Back Bay was not entirely open water - there were apparently low islands of grass. Assuming this map to be correct, I suspect the boys setting off from the corner of Arlington and Beacon streets would have been forced to skate around the large island between there and the later site of Chickering's piano factory. In fact, Chickering's is shown here near the end of a sliver of water, and probably beyond where the boys skated.

Note also that there is no mention in the quote above of skating under the railroad trestles, which would have been required of anyone skating between those two sites. The blue line shows the most likely route followed by the skaters, from the edge of the Public Garden, under the Boston & Providence trestle, and then turning right and running between that trestle and the shore of the South End, under the Boston & Albany trestle, and on as far as open ice allowed. The author comments that to go the other way, towards Gravelly Point and the dam, one would approach fast running water as the tide shifted, which kept the ice thin or entirely open, and thus was a great danger.

And now, from skating to coasting:

Of course, the winter sport par excellence was coasting, and those Boston boys whose boyhood was at the zenith in the fifties include coasting, as it was then practiced, among the lost arts. If any of the youngsters of to-day are inclined to laugh at this statement, let any one of them, athlete though he may be, take a running start of from three to ten yards at full speed with the sled following at the end of its cord, and when sufficient impetus has been acquired, throw it ahead, letting the line fall along the seat, at the same time launching his body, curved bow-wise, forward through the air, alighting breast first, with no apparent effort, jar, or retardment of speed as softly as a falling snowflake, upon the flying sled as it shoots underneath. This would be called pretty, acrobatic feat to-day, but was too common then to attract special notice. That's the difference.

All coasting in those days was racing, pure and simple. Prominent sleds were as well known among the boys as race horses and yachts are today, and on any given Saturday afternoon hundreds of spectators might be seen hedging in the "Long Coast," which ran from the corner of Park and Beason streets to teh West Street entrance and as much farther along Tremont Mall as one's impetus would carry him. A squad of coasters would be bunched together at the top of the coast, holding their sleds like dogs in leash, waiting for some "crack" to lead off. As he straightened himself and started on his run with the cry of "Lullah!" to clear the way, it was the signal for all to follow, and one after another would string out from the bunch after him, in rapid succession, each keen to pass as many of those ahead as possible,the lesser lights being careful not to start until the "heavyweights" had sped on their way.

The walk back uphill was made interesting by discussing the merits, faults, lines, etc., of the noted sleds, and if, as often happened, invidious comparisons were made between a "South End" and a "West End" sled, a lively and not altogether unwelcome scrap, then and there, was usually the logical outcome.

Sleds (the first-class ones) were made with much care and skill, and cost proportionately. Natural black walnut was a favorite material, finished either with a fine dead polish or a bright surface, varnished with as much care as a coach; the name, it it bore one, was usually a fine specimen of lettering in gold or bright colors. The model was carefully planned, and the lines were graceful and a delight to teh eye of a connoisseur. Black enameled leather, bordered by gold or silver headed tacks, made a popular seat, and the "irons," as they were called, were made of the best "silver steel," whatever that meant. They were kept burnished like glass, with constant care and fine emery and oil, and a streak of ashes or a bare spot was avoided as a yacht steers clear of rocks.

The amount of "spring" given to the irons was also a matter of moment, and a nice gradation of the same was thought to have influence on the speed; it certainly added greatly to one's bodily comfort.

"Let's see your irons" was a common request, and the owner thus honored would jerk his sled up on its hind legs, so to speak, wipe ff the steel with mitten or handkerchief, and show off the bright surface with much pride.

The most popular coasts were the "Long Coast' already mentioned, the Joy Street coast, Beacon Street Mall, and the "Big" or "Flagstaff" Hill, the flagstaff standing on the spot now graced by the Soldiers' Monument. The hill was much higher than it is now, the ground around it having been raised in recent years. Many of the boys will recall the evenings spent on Mount Vernon and Chestnut streets and Branch avenue, - the latter known as "Kitchen" street.

Fancy a laughing, shouting crowd, in these days of police surveillance, coasting down public streets until eleven o'clock at night! But the Civil War came and changed many things, coasting among the rest. Most of the laughing, careless crowd enlisted at the first note of the country's call, and their boyhood came to a sudden end as the sound of drum and fife stirred all hearts to sterner things. Some came back, but many, alas, stayed behind with the great silent army, and it is for us who are left to keep their memories green until we too are enlisted in the same ranks.

It will, I am sure, be of some interest to may who remember those days, to see once more the old familiar names of a few of the crack sleds of Boston at that period, and to have recalled to their minds who the owners of them were.

Wivern - Bob Clark

Raven - Arthur Clark

Brenda - Dan Sargent

Charlotte - Alfred Greenough

Comet - Frank Wells

Southern Cross - Frank Lawrence

Eagle - Jim Lovett

Arrow - John Muliken

Wild Pigeon - Ned Kendall

Tom Heyer - Jack Carroll

Titania - Nate Appleton

Multum in Parvo - Frank Peabody

Cave Adsum - Ned Amory

Dancing Feather - Charlie Greenough

Flying Childers - Frank Wildes

Juniata - Horace Bumstead

Trustee - Charlie Chamberlin

Santiago - Dick Robbins

Whiz - Will Freeman

Flirt - Horace Freeman

Scud - Eben Dale

Flying Cloud - Billy Fay

Cygnet - Jim Chadwick

Alma - Fred Crowninshield

Tuscaloosa - Horatio Curtis

Viking - Edgar Curtis

Moby Dick - Henry Alline

Of course there were many sleds equally fine which bore no name; prominent among this latter class should be mentioned the one owned by Tom Edmands and also one which was made and owned by Charlie Lovvett, both of them beautiful in grace, workmanship, and finish. There was one sled, named the "Edith," which always appealed to me as being more nearly perfect than any that I can remember. I cannot recall the owner's name, but I fear that whenever I saw this sled the tenth commandment was handled pretty roughly.

I can well imagine the boys and the pride they took in their sleds. The names sound like sailing ships - so romantic. I found a single reference to Tom Heyer as America's first boxing champion, although it will take some off-line digging to verify and elaborate on the fact. The reference to the 'great silent army' put a lump in my throat, and made the entire passage worth reading on its own.